Table of Contents

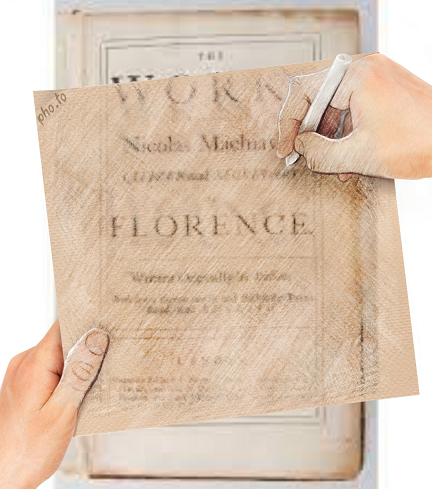

Machiavelli

This essay is a kinda ‘greatest hits’ and mashup of Machiavelli’s The Prince and Discourses on Livy. I wrote it for me to improve my retention but you can have it too.

The Discourses on Livy is my favorite of Machiavelli’s three political books, the others being The Prince and the Florentine Histories.

Discourses on Livy is his contemporary, contemporary being late 1400’s and early 1500’s, observations drawn from the histories of ancient Rome authored by Livy.

In this essay I’ll skip around a good bit because both the Prince and Discourses on Livy are not linear, they do not progress logically along a familiar narrative style. He wanders and so will I.

Discourses on Livy is divided into three sections, roughly they are:

- Matters of internal politics

- Military affairs and international politics

- For the third Machiavelli states no particular objectives.

notes:

- When quoting from The Prince I cite using only chapters, when quoting from Discourses on Livy I cite using the book number and chapter.

- I am sure I have made mistakes along the way in citing book, chapter, quote and ‘what does it mean’. It’s okay, don’t lose sleep on it and neither will I.

- I will skip some chapters, see note b. re: ‘sleep’.

- This essay is very imperfect. I know this, and now you do too.

- There is no ‘perfect’ way to sum up the Prince and Discourses, this essay takes the essence of a flower so that you can have it’s delightful smell always be fresh upon you.

Let’s begin…

I quote from the preface of Discourse on Livy: “I shall be bold to speak freely all I think, both of old times and of new, in order that the minds of the young who happen to read these my writings, may be led to shun modern examples, and be prepared to follow those set by antiquity whenever chance affords the opportunity. For it is the duty of every good man to teach others those wholesome lessons which the malice of Time or of Fortune has not permitted him to put in practice; to the end, that out of many who have the knowledge, some one better loved by Heaven may be found able to carry them out.”

The Use of Good Cruelty, Bad Cruelty. Spectacle, Shock and Awe

I’m going to linger on a theme that runs through Machiavelli, the Prince, Discourses on Livy and also his Florentine Histories, the use of cruelty.

Rather than treating violence as an evil, Machiavelli demystifies it and views it as a political tactic. Proposing an embodied and materialist analysis of how violence operates, what its causes and effects, phenomenal forms, targets, mechanisms, and circuits are, he makes political violence thinkable.

In doing so, he puts forward a historical and political perspective that deflates, depersonalizes, and demoralizes violence in politics, three moves that are crucial for a political reckoning with questions of violence.

Machiavelli is an analyst, advocate, and critic of violence. As an analyst, he probes the causes, dynamics, and functions of violence in the formation and reproduction of states. As an advocate, he defends particular modes of violence – as politically justified while denouncing gratuitous bloodshed. And as a critic, he offers an abiding challenge to moral and ontological approaches to political violence.

A Machiavellian perspective calls into question a number of presuppositions that inform modern liberal and democratic political discourses. It challenges the idea that political violence is an index of social disintegration and political disorder. It calls into question the liberal vision of political modernity as an epochal effort to contain violence.

Here we will spend a few assorted moments inside The Prince.

From Chapter 7 of The Prince. “When Cesare Borgia occupied the Romagna he found it under the rule of weak masters, who rather plundered their subjects than ruled them, and gave them more cause for disunion than for union, so that the country was full of robbery, quarrels, and every kind of violence; and so, wishing to bring back peace and obedience to authority, he considered it necessary to give it a good governor. Thereupon he promoted Messer Ramiro d’Orco a swift and cruel man, to whom he gave the fullest power. This man in a short time restored peace and unity with the greatest success. Afterwards the duke considered that it was not advisable to confer such excessive authority, for he had no doubt but that he would become odious, so he set up a court of judgment in the country, under a most excellent president, wherein all cities had their advocates. And because he knew that the past severity had caused some hatred against himself, so, to clear himself in the minds of the people, and gain them entirely to himself, he desired to show that, if any cruelty had been practised, it had not originated with him, but in the natural sternness of the minister. Under this pretence he took Ramiro, and one morning caused him to be executed and left on the piazza at Cesena with the block and a bloody knife at his side. The barbarity of this spectacle caused the people to be at once satisfied and dismayed.“

And, from chapter 8 of The Prince, Machiavelli makes note of ancient history “Some may wonder how it can happen that Agathocles, and his like, after infinite treacheries and cruelties, should live for long secure in his country, and defend himself from external enemies, and never be conspired against by his own citizens; seeing that many others, by means of cruelty, have never been able even in peaceful times to hold the state, still less in the doubtful times of war. I believe that this follows from severities being badly or properly used. Those may be called properly used, if of evil it is possible to speak well, that are applied at one blow and are necessary to one’s security, and that are not persisted in afterwards unless they can be turned to the advantage of the subjects. The badly employed are those which, notwithstanding they may be few in the commencement, multiply with time rather than decrease. Those who practise the first system are able, by aid of God or man, to mitigate in some degree their rule, as Agathocles did. It is impossible for those who follow the other to maintain themselves.”

Still in Chapter 8 of The Prince, Machiavelli returns to the present, “Hence it is to be remarked that, in seizing a state, the usurper ought to examine closely into all those injuries which it is necessary for him to inflict, and to do them all at one stroke so as not to have to repeat them daily; and thus by not unsettling men he will be able to reassure them, and win them to himself by benefits. He who does otherwise, either from timidity or evil advice, is always compelled to keep the knife in his hand; neither can he rely on his subjects, nor can they attach themselves to him, owing to their continued and repeated wrongs. For injuries ought to be done all at one time, so that, being tasted less, they offend less; benefits ought to be given little by little, so that the flavor of them may last longer.”

And on capturing a land, how the use of cruelty must be reserved and ready, because, quoting Machiavelli “And above all things, a prince ought to live amongst his people in such a way that no unexpected circumstances, whether of good or evil, shall make him change; because if the necessity for this comes in troubled times, you are too late for harsh measures; and mild ones will not help you, for they will be considered as forced from you, and no one will be under any obligation to you for them.”

To understand the uses of cruelty, good and bad, Machiavelli elaborates with these crucial quotes from The Prince, Chapter 12.

“Coming now to the other qualities mentioned above, I say that every prince ought to desire to be considered clement and not cruel. Nevertheless he ought to take care not to misuse this clemency. Therefore a prince, so long as he keeps his subjects united and loyal, ought not to mind the reproach of cruelty; because with a few examples he will be more merciful than those who, through too much mercy, allow disorders to arise, from which follow murders or robberies; for these are wont to injure the whole people, whilst those executions which originate with a prince offend the individual only.”

“Upon this a question arises: whether it be better to be loved than feared or feared than loved? It may be answered that one should wish to be both, but, because it is difficult to unite them in one person, it is much safer to be feared than loved, when, of the two, either must be dispensed with. Because this is to be asserted in general of men, that they are ungrateful, fickle, false, cowardly, covetous, and as long as you succeed they are yours entirely; they will offer you their blood, property, life, and children, as is said above, when the need is far distant; but when it approaches they turn against you.”

“Nevertheless a prince ought to inspire fear in such a way that, if he does not win love, he avoids hatred.”

“Returning to the question of being feared or loved, I come to the conclusion that, men love according to their own will and fearing according to that of the prince, a wise prince should establish himself on that which is in his own control and not in that of others; he must endeavor only to avoid hatred, as is noted.”

Discourses on Livy and The Prince. A mashup of themes and Chapter summaries

These summaries will mostly cover Discourses on Livy, the (much) larger of his two political science books. The Prince is also in this mix but its used to emphasize points he makes in Discourses.

Book I

Book One, Chapter one begins by explaining how a city is formed, which is done by either natives to the area or foreigners, citing specific examples such as Athens and Venice.

He then tries to determine what type of republic Rome was, which he states was mixed with the qualities of aristocrats and principality.

Machiavelli is interested in the strengths and weaknesses of different forms of government. Principality, aristocracy, and democracy, and their corrupted forms of tyranny, oligarchy, and anarchy.

He sees something bad in all of them:

The corrupt ones are bad, of course, from their nature, but the good ones are also defective on account of their generally brief duration. Their very fragility and instability means that they cannot really be trusted, and so aiming for a pure form of any of those three will lead to a city’s downfall, either now or later.

What is the best constitution is the mixed constitution, as Sparta first showed and as Rome perfected. The strength of mixed governance lies in the fact that it aims to take the best from each other form of government, therefore reinforcing its defenses against an otherwise inevitable decline into revolution and disorder.

Machiavelli then delves into more historical events.

The Tarquins, the last kingdom of Rome, were expelled by Brutus, 500 years before another Brutus dispatched Julius Caesar. For a brief time there seemed to be peace and alliance between the Romans and the plebs, but this was short lived and without the Tarquin control, elites were unrestrained against the plebs.

Machiavelli explains that freedom becomes an issue once a type of government shifts. Questioning what mode a free state can be maintained in a corrupt city, he states that Rome had firm laws, which kept the citizens checked.

He then goes into a discussion of the rulers of Rome and how a strong or weak Prince can maintain or destroy a kingdom. He continues, to say that after a weak prince a kingdom could not remain strong with another weak prince.

The book then slightly shifts focus to discussing the reformation of a state. Machiavelli explains that if one wants to change a state they must keep some elements of the previous state.

He then conveys that having a dictatorial authority was beneficial for the City of Rome because, for instance, Caesar was honest with this tyranny. Continuing with this, weak republics are not truly able to make important decisions and that any change will come from necessity.

Machiavelli stresses a correlation between the freedom of the founders and the constraints placed on the people.

If, as in the case of Rome or Alexandria, the climate and location of the city is agreeable, then the laws must be harsh enough that they impose “necessities” on the people that would not be there otherwise. So if you live in a place where farming is easy, you should have to undergo military exercises to toughen you up. Otherwise, the city will collapse into idleness and decadence. The glory of Rome was that this collapse was postponed for quite a while, all thanks to strict laws.

Book One, Chapter 2: Stressing the value of civil law as a necessary guide for human actions: “men never work any good unless through necessity, but where choice abounds and one can make use of license, at once everything is full of confusion and disorder. Therefore it is said that hunger and poverty make men industrious, and the laws make them good.”

A wise legislator, he warns, must frame the laws assuming that “all men are wicked,” and that they will always behave with malignity, if they have the opportunity.

Book One, Chapter 4 titled: “That the Dissensions between the Senate and Commons of Rome, made Rome free and powerful.”

Machiavelli does not believe that Rome was undone by the competition between its elites and its people, the Senate and the plebs. He thinks that the social tension between those groups, potentially

leading to disorder and even violence, engendered the very laws that preserved the freedom of Roman society as a whole. he argues that the two humors (nobility and people) must be balanced out properly.

Book One, Chapter 6: “… one inconvenience can never be suspended without another’s cropping up.” This is a general maxim of human social life. No social or political endeavor is ever really “clean.”

Therefore, we should pick whichever plan is least messy and most expedient within a given political situation. The ‘Ideals’ of stability, steadiness, and balance are all well and good, but history reveals them as illusions, mockeries. If our goal is to keep a republic alive and healthy, it must be in motion.

The republic must grow. Peace, tranquility, stasis are signs of death, not political vivacity.

Machiavelli returns to ancient Rome as an example, a city full of internal strife that commutes that energy into external consumption—growth, expansion, generation of new tension, and therefore an engine of freedom.

Book One, chapter 8 he discusses treachery expressed thru calumny, false accusations offered with little or no evidence. He points to the example set by the Romans as a remedy: “The Romans demonstrated exactly how false accusers must be punished. Indeed, they must be turned into public accusers, and when the public indictment is found true, either reward them or avoid punishing them, but when it is found false, punish them as Manlius was punished.” Manlius was thrown from the Tarpeian Rock. To preserve justice, a state must always uphold the rule of law.

A recurrent theme throughout these Discourses concerns the risks and advantages of “regime change” of efforts to alter the form of government of a people. Machiavelli understands that the virtue of a people (or its absence) is relevant to the type of government appropriate to that people. Again, from Book One, chapter 8, “different institutions and ordinances are needed in a corrupt State from those which suit a State which is not corrupted; for where the matter is wholly dissimilar, the form cannot be similar.”

Machiavelli says that therefore, no one form of government is suitable for all. The attempt to introduce democracy to a polity that has previously been under a powerful prince is especially fraught, and one must, in Machiavelli’s words “kill the sons of Brutus” — that is, remove all those who had specially benefited under the prince, lest they conspire against the new order. That this counsel might be pertinent to our contemporary affairs has not been entirely overlooked.

Book One, chapter 18: “Just as good customs require laws in order to be maintained, so laws require good customs in order to be observed.” For Machiavelli the rule of law is the indispensable basis of any form of legitimate government. He contrasts in fact political life with tyranny understood as authority unbound by laws. A corrupt city is precisely one where laws are disobeyed, and neither laws nor institutions have the force to check widespread license.

Book One, chapter 25 “Whoever takes upon him to reform the government of a city, must, if his measures are to be well received and carried out with general approval, preserve at least the semblance of existing methods, so as not to appear to the people to have made any change in the old order of things; although, in truth, the new ordinances differ altogether from those which they replace. For when this is attended to, the mass of mankind accept what seems as what is; nay, are often touched more nearly by appearances than by realities.”

Book One, Chapter 29, about gratitude and vengeance he quotes Roman historian Tacitus “Men are more inclined to repay injury than kindness: the truth is that gratitude is irksome, while vengeance is accounted gain.”

Book One, Chapter 34: In his defense of the rule of law, Machiavelli asserts that republics must be capable of facing even extraordinary situations by legal means. He cites the Roman dictatorship and stresses that without that institution that republic would have survived “extraordinary accidents” only with difficulty. Even more praiseworthy was the example of the Republic of Venice, “excellent among modern republics,” that “has reserved authority to a few citizens who in urgent needs can decide, all in accord, without further consultation.” What makes this institution excellent is precisely that it permits a republic to face situations of emergency without breaking the statutes. Even though extraordinary measures may do good in some cases, yet, Machiavelli warns, “the precedent thus established is bad, since it sanctions the usage of dispensing with constitutional orders for a good purpose, and thereby makes it possible, on some plausible pretext, to dispense with them for a bad purpose.” Therefore “no republic is ever perfect, unless by its laws it has provided a remedy for all contingencies and for every eventuality, and determined the method of applying it.”

Book One, Chapter 43 “To the question of whether nobles guard freedom more effectively than do the people.” He asks “But reverting to the question, which class of citizens is more mischievous in a republic – those who seek to acquire or those who fear to lose what they have acquired already.”

Book One, Chapter 45 “Nothing, I think, is of worse example in a republic, than to make a law and not to keep it; and most of all, when he who breaks is he that made it.”

By way of illustration he cites the example of Horatius, a man celebrated for his courage and credited with saving the city from destruction, but then subsequently found guilty of homicide and punished in accordance with the law.

Book One Chapter 47: Titled “That though Men deceive themselves in Generalities, in Particulars they judge truly.” I am including a large segment of this chapter.

“…Pacuvius Calavius, who at this time filled the office of chief magistrate, perceiving the danger, took upon himself to reconcile the contending factions. With this object he assembled the Senate and pointed out to them the hatred in which they were held by the people, and the risk they ran of being put to death by them, and of the city, now that the Romans were in distress, being given up to Hannibal. But he added that, were they to consent to leave the matter with him, he thought he could contrive to reconcile them; in the meanwhile, however, he must shut them up in the palace, that, by putting it in the power of the people to punish them, he might secure their safety.

The senate consenting to this proposal, he shut them up in the palace, and summoning the people to a public meeting, told them the time had at last come for them to trample on the insolence of the nobles, and requite the wrongs suffered at their hands; for he had them all safe under bolt and bar; but, as he supposed they did not wish the city to remain without rulers, it was fit, before putting the old senators to death, they should appoint others in their room. Wherefore he had thrown the names of all the old senators into a bag, and would now proceed to draw them out one by one, and as they were drawn would cause them to be put to death, so soon as a successor was found for each. When the first name he drew was declared, there arose a great uproar among the people, all crying out against the cruelty, pride, and arrogance of that senator whose name it was. But on Pacuvius desiring them to propose a substitute, the meeting was quieted, and after a brief pause one of the commons was nominated. No sooner, however, was his name mentioned than one began to whistle, another to laugh, some jeering at him in one way and some in another. And the same thing happening in every case, each and all of those nominated were judged unworthy of senatorial rank. Whereupon Pacuvius, profiting by the opportunity, said, “Since you are agreed that the city would be badly off without a senate, but are not agreed whom to appoint in the room of the old senators, it will, perhaps, be well for you to be reconciled to them; for the fear into which they have been thrown must have so subdued them, that you are sure to find in them that affability which hitherto you have looked for in vain.” This proposal being agreed to, a reconciliation followed between the two orders; the commons having seen their error so soon as they were obliged to come to particulars.

Book One, Chapter 54: Explaining that an effective way to manipulate the masses is to find someone who “appears” serious, reverend, and authoritative. The appearance of such a man can be used to restrain and redirect the energy of the restless multitude. Machiavelli writes that “nothing tends so much to restrain an excited multitude as the reverence felt for some grave person, clothed with authority, who stands forward to oppose them.”

Towards the end of Book One, Machiavelli adds that great accidents that occur in a city usually come with some kind of sign. This sign could be divine or seen through a revelation. He gives the particular example that in Florence right before the death of Lorenzo de’ Medici the Elder, a cathedral was hit by lightning.

The role of Fortune plays a significant role in Discourses. Machiavelli expresses an interesting view of Fortune and its role in shaping history. Fortune acted as a similar force to the role of gods, yet it was completely different in the sense that religion was man made and fortune existed naturally and benefited those who demonstrated good virtues.

Book II

Book two begins with an introspective preface, is he enamored with Rome as it was, or as he wished it to be?

Is his praise antiquarian nostalgia?

Many complain about the present by comparing it to an idealized past, but their ideals may not correlate to the past reality. Often the present epoch does indeed represent an improvement on what came before. But our incomplete knowledge of the past allows us to preserve only the best of it—only the exemplars of virtue, against which we then measure the mediocrity of today. This is not a reasonably grounded way of doing things.

He responds to his own line of questioning by arguing, to himself, that the political ‘virtue’ of the Roman Republic and Empire is beyond debate. And so he feels justified in looking to it for exemplars. Even though he himself does not see such ancient learning being put into practice any time soon, he hopes that the youth of the future will be better situated to act on his ideas.

Still in the preface, Machiavelli includes a history of imperial virtue, transitioning from the ancient Mesopotamian Empires to Rome, then being “scattered” across the Franks, the Turks, and more recently the German HRE. The situation for the Italians and Greeks is much worse, however, since they face a present epoch defined by subjugated to external forces: either the ultramontane French / HRE or the Muslim Turks. The underlying idea here is that vice and virtue always exist in about the same measure throughout history; it is only their locations that shift.

All human affairs are always “in motion.” Political states, too, must be seen as dynamic: ascending or descending over given stretches of time. The political theorist must account not just for the fact of such ‘political motion’ but perhaps even its desirability

The narrative movement of Discourses from Book One to Book Two is a transition from Rome’s internal relations to its external relations. This coincides with a move from the republic to the empire. He wonders ‘How did Rome acquire its empire? By fortune or by virtue?’ Although many have said ‘by fortune’ Machiavelli is convinced that virtue played a large part.

Many things can appear to be consequences of ‘fortune,’ even though they are situations created by previous acts of political virtue. What motivated all of this political virtue among the Romans? An insatiable desire to defend their “freedom.”

He stays inside ancient Rome and explains that it was the political virtue—virtù endowed with thumos, of the Romans that was driven by their thirst for freedom.

Political freedom is the independence to decide internal policy, free of outside influence.

But the furtherance of freedom was the expansion of political power to influence other areas. Freedom does not hold back; it dominates.. The ancients, in short, loved their freedom.

He wonders when did ‘we’ (Florence) lose our taste for freedom?

He believes that “Europe” (Florence) taste for freedom has diminished as the interpreters of its religion, Christianity, have emphasized passive traits rather than active force.

Book Two, Chapter one debates whether Virtue or Fortune had more of a cause of the empire that the Romans acquired. There were many opinions equally distributed to both sides, and there is not final consensus on which had more of a cause, virtue or fortune.

Book Two, Chapter two “Our religion [Christianity] has glorified humble and contemplative more than active men. It has then placed the highest good in humility, abjectness, and contempt of things human; the other [ancient religion] placed it in greatness of spirit, strength of body, and all other things capable of making men very strong. And if our religion asks that you have strength in yourself, it wishes you to be more capable of suffering than of doing something strong. This mode of life thus seems to have rendered the world weak and given it in prey to criminal men, who can manage it securely, seeing that the collectivity of men, so as to go to paradise, think more of enduring the beatings than of avenging them. And although the world appears to be made effeminate and heaven disarmed, it arises without doubt more from the cowardice of the men who have interpreted our religion according to idleness and not according to virtue.”

As a result, the world has grown “weak” and even “effeminate.” ‘Manly’ virtue has given way to passive patience. Good Christians await the eschaton rather than fighting for their land, for freedom in the here and now.

The fault cannot, of course, lie with Christianity itself. Rather, it lies with bad interpreters and educators. Men of cowardice have taught Christianity as a religion of “idleness,” instead of a call to virtue.

Machavelli believes that states that live according to idleness and passivity meet predictable ends,. Vigorous, virtuous, thumotic states, on the other hand, grow and attain empire—make profits and multiple riches. The real state, the state in motion, should look like the latter.

Book Two, Chapter five is titled: “The changes of religion and of languages, together with the occurrence of deluges and pestilences, destroy the record of things.” and talks about how memories can be lost due to issues such as the destruction or neglect of language, a political regime destroying rituals and customs, and natural events such as floods, or even plague.

Book Two, Chapter six talks about how the Romans went about making war.

One of Rome’s key innovations was to come up with new, prudent ways of waging wars, even if those ways differed from universal consensus.

a. Fight “short and massive” wars.

b. Distribute booty to the benefit of the state treasury.

c. Establish colonies

I wander into the Prince for just this quote, and then back to Discourses. “Two causes which lead to wars being made against a republic, your desire to be its master, or your fear of it being yours. And he who looks carefully into the matter will find that in all human affairs, we cannot rid ourselves of one inconvenience without running into another. So that if you would have your people numerous and warlike, to the end that with their aid you may establish a great empire, you will have them of such a sort as you cannot afterwards control at your pleasure; while should you keep them few and unwarlike, to the end that you may govern them easily, you will be unable, should you extend your dominions, to preserve them, and will become so contemptible as to be the prey of any who attack you. For which reason in all our deliberations we ought to consider where we are likely to encounter least inconvenience, and accept that as the course to be preferred, since we shall never find any line of action entirely free from disadvantage.”

Book 2, Chapter 7: “But when a country is armed as Rome was and Switzerland now is, the closer you press it, the harder it is to subdue; because such States can assemble a stronger force to resist attack than for attacking others”

It is important to consider whether their populace is armed or not. The ancient Romans and the contemporary Swiss both keep their people militarized constantly, whereas states like France and the Italian city-states spend money to raise armies when necessary. The former kind of states should avoid far-flung wars and slowly expand from their center of power outward; the latter should aim to engage only in far-off wars, since their soft center remains so vulnerable.

Book Two, Chapter 10 talks about how the common opinion of money being the sinew of war is very wrong. He asserts that it is easier to get gold if you have good soldiers than it is to get good soldiers if all you have is gold. This continues an earlier line of Machiavellian thought: it is best to build up a loyal fighting force from within, rather than trying to buy mercenary loyalties

Book Two, Chapter 13 talks about how a person comes from base to great fortune more through fraud than through force. He thinks that fraud is just quicker and easier, so force is not needed.

Book Two, Chapter 14. “It is better that a thing be taken from you by force than yielded through fear of force. For if you yield through fear and to escape war, the chances are that you do not escape it; since he to whom, out of manifest cowardice you make this concession, will not rest content, but will endeavor to wring further concessions from you, and making less account of you, will only be the more kindled against you. At the same time you will find your friends less zealous on your behalf, since to them you will appear either weak or cowardly. But if, so soon as the designs of your enemy are disclosed, you at once prepare to resist though your strength be inferior to his, he will begin to think more of you, other neighboring princes will think more; and many will be willing to assist you, on seeing you take up arms, who, had you relinquished hope and abandoned yourself to despair, would never have stirred a finger to save you.”

Book Two, Chapter 15 claims that the resolutions of weak states will always be ambiguous, and that slow decisions, no matter who or what is making them, are always hurtful.

Book Two, Chapter 20 talks about the dangers to a prince or republic that avails itself of auxiliaries or a mercenary military.

Book Two, Chapter 26 claims vilification and abuse generate hatred against those who use them, without any utility to them. Machiavelli is saying that the abuse that men do to women is something that brings hatred not only from the victim, but from everyone who hears about it as well.

Book Two, Chapter 27, titled “That prudent Princes and Republics should be content to have obtained a Victory; for, commonly, when they are not, theft-Victory turns to Defeat.”

Machiavelli emphasizes that wars must be won, the victory completed. Imperial conquest should be sufficient in and of itself. There is no need to add gloating or hubris or over-consumption to the mix. Often, healthy imperial expansion is actually impeded by such pride fueled overreach.

Book Two, Chapter 28 says how dangerous it is for a Republic or a Prince not to avenge an injury done against the public or against a private person. This chapter is titled “That to neglect the redress of Grievances, whether public or private, is dangerous for a Prince or Commonwealth.”

As this chapter includes some history of Alexander the Great, I’ll include this whole section.

Whereof we have no finer or truer example than in the death of Philip of Macedon, the father of Alexander. For Pausanias, a handsome and high-born youth belonging to Philip’s court, having been most foully and cruelly dishonoured by Attalus, one of the foremost men of the royal household, repeatedly complained to Philip of the outrage; who for a while put him off with promises of vengeance, but in the end, so far from avenging him, promoted Attalus to be governor of the province of Greece. Whereupon, Pausanias, seeing his enemy honoured and not punished, turned all his resentment from him who had outraged, against him who had not avenged him, and on the morning of the day fixed for the marriage of Philip’s daughter to Alexander of Epirus, while Philip walked between the two Alexanders, his son and his son-in-law, towards the temple to celebrate the nuptials, he slew him.

This instance nearly resembles that of the Roman envoys; and offers a warning to all rulers never to think so lightly of any man as to suppose, that when wrong upon wrong has been done him, he will not bethink himself of revenge, however great the danger he runs, or the punishment he thereby brings upon himself.”

Book III

Book 3 is an assortment of subjects but in general is about the renewal of regimes.

Machiavelli observes that changes in regimes are inevitable, human things are always in motion. The question is how to manage change for the sake of the overall longevity of the whole.

The safest way to manage change is this: to periodically renew a regime by drawing it back towards its beginnings. There is safety in the origin. This doesn’t mean actually going back in time or ‘primitivizing’ society, but instead coming up with new political orders that renew and re-energize the spirit of the regime, as communicated in its founding. Such renewal can come via external accident such as a transformative invasion or internal prudence.

One model for this renewal would actually be the renewal of Christianity itself by the mendicant orders in the thirteenth century. What we need are periodic appearances of the political equivalents of Franciscans and Dominicans.

Book Three, Chapter 1 is titled: “If one wishes a sect or republic to live long, it is necessary to draw it back often towards its beginning.” Machiavelli admits that “all worldly things” have a natural ending. If any of these worldly things are altered and changed from its normal course “it is for its safety and not to its harm.”

Machiavelli, however, desires to talk about exceptions to this rule “mixed bodies, such as republics and sections.” For these things “alterations are for safety that lead them back toward their beginnings.”

Machiavelli is referring to the state of a republic when he ends the first paragraph, declaring that “it is a thing clearer than light that these bodies do not last if they do not renew themselves.” “all the beginnings of sects, republics, and kingdoms must have some goodness in them, by means of which they must regain their reputation and their first increase.”

This return toward the beginning is done either through prudence from outside of the republic or from within the republic. Machiavelli cites an example from Roman history, when the Gauls, referring to them as the French, sacked Rome in 387 B.C. He believes that the Gauls’ aggression was necessary “if one wished that that it be reborn and, by being reborn, regain new life and new virtue, and regain the observance of religion and justice, which were beginning to be tainted in it.”

“this good emerges in republics either through the virtue of a man or through the virtue of an order.”

“the orders that drew the Roman republic back toward its beginning were the tribunes of the plebs, the censors, and all the other laws that went against the ambition and the insolence of men.“

“Unless something arises by which punishment is brought back to their memory and fear is renewed in their spirits, soon so many delinquents join together that they can no longer be punished without danger.”

This quote from The Prince better informs this point as it pertains also to a war fought from within by the population and its factions and also to lands that are ruled “You must know, then, that there are two methods of fighting, the one by law, the other by force: the first method is that of men, the second of beasts; but as the first method is often insufficient, one must have recourse to the second.“

Returning to Discourses.

Book Three, Chapter 3 states “That it is necessary to kill the sons of Brutus if one wishes to maintain a newly acquired freedom.” Citing one of Junius Brutus’s ancestors, who sentenced his own sons to death when they threatened the young Roman Republic, Machiavelli writes that “after a change of state, either from republic to tyranny or from tyranny to republic, a memorable execution against the enemies of present conditions is necessary. Whoever takes up a tyranny and does not kill Brutus, and whoever makes a free state and does not kill the sons of Brutus, maintains himself for little time.”

From this quote I venture to another source, the Prince, chapter 22. “And he who becomes master of a city used to being free and does not destroy her can expect to be destroyed by her.”

Returning to discourses.

Book Three, Chapter 4 titled “A prince does not live secure in a principality while those who have been despoiled of it are living.”

Machiavelli begins the chapter citing Livy “The death of Tarquin Priscus”, caused by the sons of Ancus, and the death of Servius Tullius, caused by Tarquin the Proud, show how difficult and dangerous it is to despoil one individual of the kingdom and to leave him alive, even though on might seek to win him over by compensation.”

This event functions as advice to future princes “every prince can be warned that he never lives secure in his principality as long as those who have been despoiled of it are living.”

Book Three, Chapter 6 pertains to conspiracy. Machiavelli believes that the danger of conspiracy must be raised as quote: “many more princes are seen to have lost their lives and states through these than by open war. For to be able to make open war on a prince is granted to few; to be able to conspire against them is granted to everyone.”

Another motivator for conspiracy is when a man feels the desire to free his fatherland from whoever has seized it. This was primarily what drove Brutus and Cassius to conspire against Caesar.

Machiavelli gives examples of how any man can create a conspiracy, ranging from the nobleman who assassinated King Philip of Macedon to the Spanish peasant who stabbed King Ferdinand in the neck. He asserts that all conspiracies are made by great men of those very familiar to the prince.

Though any man can lead a conspiracy, only great men can perfectly execute it. Dangers are found in conspiracies at three times, first in its planning, then in the deed, and third after the act.

Machiavelli raises the Pisonian conspiracy against Nero and uses a contemporary conspiracy that Florence had just endured, the Pazzi conspiracy against Lorenzo and Giuliano de’ Medici. He notes that failure to execute a conspiracy results only from the executor’s own cowardice and lack of spirit.

Many hazards attend efforts to change social institutions: From Book Three, chapter 8 “It is no less arduous and dangerous to attempt to free a people disposed to live in servitude, than to enslave a people who desire to live free.”

Book Three, Chapter 10 pertains to the fact that “a captain cannot flee battle when the adversary wishes him to engage in it in any mode.”

Quoting again “If one hides in his city, far from the field of battle, he “leaves one’s country as prey to the enemy.” If one hides within the city with his army, they will be besieged, starved, and forced to surrender.”

Book Three, Chapter 13 contemplates “Which is more to be trusted, a good captain who has a weak army or a good army that has a weak captain.”

Book Three, Chapter 20 concerns the story of Camillus when he was besieging the city of the Falsci.

A schoolmaster of the noblest children of the city ventured out and offered the children to the Roman camp as slaves. Camillus refused the offer, and after binding the hands of the schoolmaster, gave rods to each of the children and escorted them back into the city while they beat him. When the Falsci heard of Camillus’s good act, they willfully surrendered the city without putting up a fight. Machiavelli concludes from the story that “Here it is to be considered with this true example how much more a humane act full of charity is sometimes able to do in the spirits of men than a ferocious and violent act.”

Book Three, Chapter 21, Machiavelli explores that “men are desirous of new things, so much that most often those who are well off desire newness as much as those who are badly off.”

Back to The Prince and why utopias, like that contemplated by Plato, are absurdities. “He who neglects what is done for what ought to be done, sooner effects his ruin than his preservation.”

Returning to Discourses.

Book Three, Chapter 25, as discussed in my preview earlier, Machiavelli states that “the most useful thing that may be ordered in a free way of life is that the citizens be kept poor.”

He recalls the story of the great Cincinnatus, who, when Rome was in grave danger, was made dictator by the Senate and saved the Republic. When the battle was over, he surrendered his power and returned to his small villa. His humbleness or “poverty” became something future Romans tried to emulate. Machiavelli concludes the chapter writing “One could show with a long speech how much better fruits poverty produced than riches.”

Machiavelli promotes a virtuous poverty that should also be cultivated amongst the citizens, even those with political power. Concentration of wealth is to the active detriment of republican cohesion.

The only question is how best, in any given context, to encourage such ‘wealth redistribution.’

Book Three, Chapter 26‘s title is “How a State is ruined because of women.” First, one sees that women have been causes of much ruin, and have done great harm to those who govern a city, and have caused many divisions in them.”

He raises the example of Lucretia, whose rape by Tarquin the Proud’s son ultimately led the exile of the Tarquin family from Rome and destruction of the Roman monarchy.

Book Three, Chapter 27, Machiavelli believes that there are three possible ways to handle the leaders of rebellion within a held city “either to kill them, as they did; or to remove them from the city; or to make them make peace together under obligations not to offend one another.”

Book Three, Chapter 28 states that “One should be mindful of the works of citizens because many times underneath a merciful work a beginning of tyranny is concealed.”

Machiavelli relates it to a moment in Roman history when there was considerable famine and the wealthy Spurius Maelius planned to distribute grain to win over the favor of the Plebs. Maelius planned to become dictator with this favor but was executed by the senate before he could do so.

Book Three, Chapter 31 states “Strong republics and excellent men retain the same spirit and their same dignity in every fortune.” If the leader of a republic is weak, then his republic will be weak.

Machiavelli raises the modern example of the Venetians, whose good fortune created a sort of “insolence” that they failed to respect the powerful states around them and lost much of their territorial holdings. Machiavelli asserts that it is necessary to have a strong military in order to have a state with “good laws or any other good thing.”

Book Three, Chapter 36, Machiavelli recalls that the Gauls were quick to start fights but in actual combat failed spectacularly. He writes that while the Roman army had fury and virtue, the army of the Gauls only had fury, which, more often than not, lead them into embarrassing battles.

Book Three, Chapter 40, Machiavelli states “Although the use of fraud in every action is detestable, nonetheless in managing war it is a praiseworthy and glorious thing, and he who overcomes the enemy with fraud is praised as much as the one who overcomes it with force.”

Fraud in war means fooling the enemy. He raises the story of Pontus, captain of the Samnites, who sent some of his soldiers in shepherds clothing to the Roman camp so that they could be lead them into an ambush where Pontus’s army was waiting.

Book Three, Chapter 42 is where we will stop, the chapter title is “That promises made through force ought not to be observed.”

Should promises made under duress be kept? No.

Once the force that pressured them is gone, such promises may be broken. Any promises whatsoever may be broken provided that the causes that led to them in the first place have now disappeared.

It is better to be the hypocrite than its dupe.

We have found our end. I hope you have enjoyed reading this as much as I enjoyed writing it.

Information without retention is not knowledge.

Audiobooks, PDF’s and Epub’s. Discourses on Livy, The Prince, Florentine Histories → Machiavelli

This audiobooks are large files so I put them on Google Drive – It downloads as a zip folder that will have all the different subfolders.

The end?