Why I study the Peloponnesian war, Thucydides, Herodotus, Language, Civil War, Tyrants, Tyrannies Turned Inwards, Historiography and so on and so on

Thucydides wrote about history’s first revolution. Who will tell the story of its last? Let it be you

Table of Contents

- Thucydidean reading list

- a. The Great Courses, The Peloponnesian War, Kenneth Harl

- b. The Peloponnesian War, Thucydides

- c. Remembering Defeat. Civil War and Civic Memory in Ancient Athens by Andrew Wolpert

- d. The Logic of Violence in Civil War by Stathis Kalyvas

- e. Thucydides and Internal War by Jonathan J. Price

- f. Tyranny and terror: the failure of Athenian democracy and the reign of the Thirty Tyrants By Lucas D. LeCaire

- g. Thucydides: The Reinvention of History By Donald Kagan

- h. Scholars and Warriors: quoting and misquoting Thucydides, by Neville Morley

- i. Thucydides’ War Narrative: A Structural Study by Carolyn J. Dewald

- j. The Great Courses, Herodotus: The Father of History, Elizabeth Vandiver

- k. Language, Stasis and the Role of the Historian in Thucydides, Sallust and Tacitus by Lydia Spielberg

- l. VIDEO: What I Read and Why I Read It

Thucydidean reading list

Notes

- I’m not writing a review of each book or item on the list. If it’s included, it’s because its included.

- I’m don’t list all of the essays and such because the point of this effort of mine is not for someone to recreate what I’ve done, but rather to share my experience and stimulate others to tell themselves a story

- The list below is forever incomplete, it also moves around into other categories of my interest which intertwine – such as propaganda, civil war, and so on and so on.

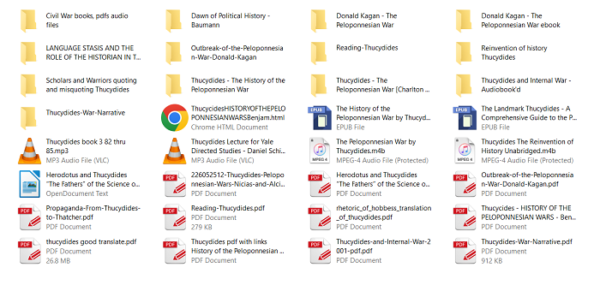

Photo 1: This is my digital “Thucydides (Peloponnesian) library“.

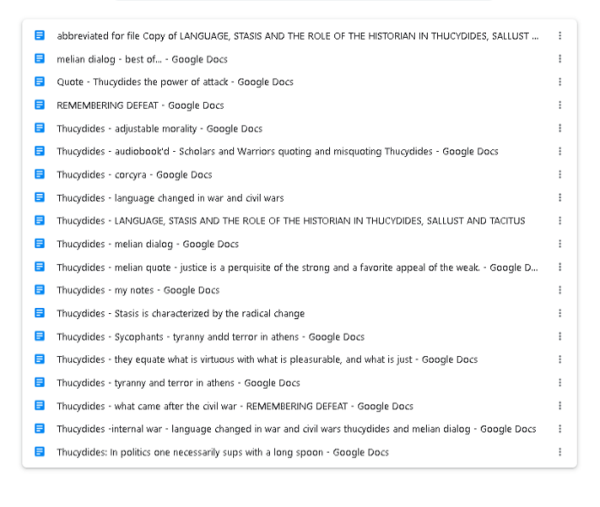

Photo 2: I take a lot of notes on what I read, it’s the chemistry of transforming information into “knowledge”.

a. The Great Courses, The Peloponnesian War, Kenneth Harl

I have read the underlying bo0k – History of the Peloponnesian War by Thucydides several times, but I think The Great Courses is a shortcut and gets you to the ‘better parts’ more expeditiously.

After reading the book I became interested in several things I encountered that I felt needed more exploration, such as tyrannies turning inwards, and about how language is trained and how civil wars spark, and how they end, and how it resolved itself in the Hellenic World and so I pursued those interests deeper, and Ive included those here for ‘our’ amusements.

b. The Peloponnesian War, Thucydides

Read any translation, don’t be ‘that person’. They’re all great.

– excerpt: Corcyra civil war: Book 3, begins at 82 – 85

(paragraph’ing is my own) (Jowett translation)

Here is a brief excerpt from Thucydides History. It was written 2000 years ago. The present and future has happened before. Read or listen:

“For not long afterwards nearly the whole Hellenic world was in commotion; in every city the1 chiefs of the democracy and of the oligarchy were struggling, the one to bring in the Athenians, the other the Lacedaemonians. Now in time of peace, men would have had no excuse for introducing either, and no desire to do so; but, when they were at war the introduction of a foreign alliance on one side or the other to the hurt of their enemies and the advantage of themselves was easily effected by the dissatisfied party

And revolution brought upon the cities of Hellas many terrible calamities, such as have been and always will be while human nature remains the same, but which are more or less aggravated and differ in character with every new combination of circumstances.

In peace and prosperity both states and individuals are actuated by higher motives, because they do not fall under the dominion of imperious necessities; but war, which takes away the comfortable provision of daily life, is a hard master and tends to assimilate men’s characters to their conditions.

When troubles had once begun in the cities, those who followed carried the revolutionary4 spirit further and further, and determined to outdo the report of all who had preceded them by the ingenuity of their enterprises and the atrocity of their revenges.

The meaning of words had no longer the same relation to things, but was changed by them as they thought proper. Reckless daring was held to be loyal courage; prudent delay was the excuse of a coward; moderation was the disguise of unmanly weakness; to know everything was to do nothing. Frantic energy was the true quality of a man.

A conspirator who wanted to be safe was a recreant in disguise. The lover of violence was always trusted, and his opponent suspected. He who succeeded in a plot was deemed knowing, but a still greater master in craft was he who detected one. [5] On the other hand, he who plotted from the first to have nothing to do with plots was a breaker up of parties and a poltroon who was afraid of the enemy. In a word, he who could outstrip another in a bad action was applauded, and so was he who encouraged to evil one who had no idea of it. The tie of party was stronger than the tie of blood, because a partisan was more ready to dare without asking why.

For party associations are not based upon any established law, nor do they seek the public good; they are formed in defiance of the laws and from self-interest.

The seal of good faith was not divine law, but fellowship in crime. If an enemy when he was in the ascendant offered fair words, the opposite party received them not in a generous spirit5, but by a jealous watchfulness of his actions6.

Revenge was dearer than self-preservation. Any agreements sworn to by either party, when they could do nothing else, were binding as long as both were powerless. But he who on a favorable opportunity first took courage, and struck at his enemy when he saw him off his guard, had greater pleasure in a perfidious than he would have had in an open act of revenge; he congratulated himself that he had taken the safer course, and also that he had overreached his enemy and gained the prize of superior ability.

In general the dishonest more easily gain credit for cleverness than the simple for goodness; men take a pride in the one, but are ashamed of the other.

The cause of all these evils was the love of power, originating in avarice and ambition, and the party-spirit which is engendered by them when men are fairly embarked in a contest. For the leaders on either side used specious names, the one party professing to uphold the constitutional equality of the many, the other the wisdom of an aristocracy, while they made the public interests, to which in name they were devoted, in reality their prize.

Striving in every way to overcome each other, they committed the most monstrous crimes; yet even these were surpassed by the magnitude of their revenges which they pursued to the very utmost, neither party observing any definite limits either of justice or public expediency, but both alike making the caprice of the moment their law.

Either by the help of an unrighteous sentence, or grasping power with the strong hand, they were eager to satiate the impatience of party-spirit. Neither faction cared for religion; but any fair pretense which succeeded in effecting some odious purpose was greatly lauded. And the citizens who were of neither party fell a prey to both; either they were disliked because they held aloof, or men were jealous of their surviving.”

(end)

c. Remembering Defeat. Civil War and Civic Memory in Ancient Athens by Andrew Wolpert

The Hellenic civil war was horrible, I became interested in ‘what it was’ and how did it resolve itself. It’s such a fascinating and important history and touches on the death of Socrates, tyrants moving their wars into legal pursuits, lawfare and orators and how do people reconcile.

“In 404 b.c.e., the Peloponnesian War finally came to an end when the Athenians, starved into submission, were forced to accept Sparta’s terms of surrender. Shortly afterward, a group of thirty conspirators with Spartan backing overthrew the democracy and established a narrow oligarchy.

Within the course of thirteen months, the oligarchs killed more than 5 percent of the citizen population and proceeded to terrorize the rest of the community by confiscating property and by banishing from the city all who were not members of their government.

After regaining control of Athens, the democratic resistance agreed to an amnesty that protected the collaborators from prosecution for all but the most flagrant crimes.

The Athenians, however, could not simply forget the past. Evident in speeches delivered in public at civic settings shortly after the reconciliation of 403, a residue of anger, fear, and distrust remained in the community.

Yet Athens did not sink into a cycle of bloodshed such as occurred elsewhere in Greece. In fact the city remained remarkably stable until Macedon dissolved the democracy nearly a century later.

The reader of Thucydides cannot help but be surprised at the outcome of the Athenian civil war. We are taught by the Corcyraean revolution the di≈culty of stopping violence once stasis erupts (Thuc. 3.69–85, 4.46–48). Athens stands in stark contrast.

If Thucydides wrote much of his work after the Peloponnesian War, perhaps he expected his account of Corcyra to draw to the reader’s attention the uniqueness of Athens. But even if this is not the case, Corcyra is a vivid reminder to us of the stakes in the Athenian reconciliation and of the consequences were it to fail.

Civil war was widespread in the rest of Greece.

For this reason, much of fourth-century philosophy was devoted to the question of how to prevent stasis. But the philosophers did not attempt to explain what citizens must do to restore civic harmony should a city su√er from stasis; they were more concerned with discovering a blueprint to prevent it from happening in the first place. Still, civil strife continued to occur, and the victims, bystanders, and collaborators were forced to carry on after brutal atrocities. With such concerns in mind, I have set out to examine how the Athenians were able to do what Corcyra and most other Greek cities could not, convinced that the answer can help us better understand the nature of Athenian democracy and show us how a community can repair the damages of a bitter civil war and heal its divisions.

Historians have advanced many explanations for the success of the reconciliation: the terms of the agreement, the political condition of the Greek world, the social and economic problems of Athens.

They have shown that revenge and retribution were not viable options, but the Athenians could have simply dismissed pragmatic considerations in order to obtain private satisfaction for past grievances. Causal explanations present the reconciliation as a fait accompli, as if there were only one possible outcome to the civil war.∂ But as Corcyra shows, pragmatic considerations do not always lead a people to chose the course of action that best serves its interests.

Whatever the reasons for reconciliation, Athens had to become a community again, and relations between the democrats and former oligarchs had to be normalized. When the Spartans demolished the Long Walls, the Athenians became vulnerable from within and without. Oligarchs in collusion with Lysander seized this opportunity to overthrow the democracy. In the period after the oligarchy of the Thirty, Athens struggled to regain its autonomy. The Athenians rebuilt the walls to protect their city from foreign threats, and they attempted to restore civic harmony.

They could not simply pick up the pieces and continue where they had left off. They needed to redefine who they were, or, to echo Loraux (1986), they needed to ‘‘reinvent’’ Athens.

Rather than explain why the reconciliation was successful, this study examines the civic speeches and public commemorations of the early fourth century to consider how the Athenians confronted the troubling memories of defeat and civil war and how they reconciled themselves to an agreement that allowed past crimes to go unpunished.

This approach helps us better appreciate changes in Athenian ideology as well as the fragility of the reconciliation. The scope of this study is roughly the first generation after the Thirty, from the peace treaty of 403 to the formation of the Second Athenian League in 378/7. A precise date to mark its end remains elusive, since the reconciliation was not a single act but a process by which the Athenians gradually (and only partially) accepted the reintegration of their city. Over time, hostilities faded and new concerns and fears dominated Athens.”

(end)

d. The Logic of Violence in Civil War by Stathis Kalyvas

This book falls outside of my studies of Thucydides and the Peloponnesian war – but it helps me better understand the ideas of ‘civil war’ that the contagions and influences of Corcyra. Here is that question again, how does a country fix itself, or fail too self correct and instead make itself prey.

I discovered this book sometime around the start of the Ukraine conflict in February 2022 and there’s a timelessness and place’lessness to it.

“By analytically decoupling war and violence, this book explores the causes and dynamics of violence in civil war. Against prevailing views that such violence is either the product of impenetrable madness or a simple way to achieve strategic objectives, the book demonstrates that the logic of violence in civil war has much less to do with collective emotions, ideologies, cultures, or “greed and grievance” than currently believed.

Stathis Kalyvas distinguishes between indiscriminate and selective violence and specifies a novel theory of selective violence: it is jointly produced by political actors seeking information and individual noncombatants trying to avoid the worst but also grabbing what opportunities their predicament affords them. Violence is not a simple reflection of the optimal strategy of its users; its profoundly interactive character defeats simple maximization logics while producing surprising outcomes, such as relative nonviolence in the “frontlines” of civil war. Civil war offers irresistible opportunities to those who are not naturally bloodthirsty and abhor direct involvement in violence.

The manipulation of political organizations by local actors wishing

to harm their rivals signals a process of privatization of political violence rather than the more commonly thought politicization of private life. Seen from this perspective, violence is a process taking place because of human aversion rather than a predisposition toward homicidal violence, which helps explain the paradox of the explosion of violence in social contexts characterized by high levels of interpersonal contact, exchange, and even trust. Hence, individual behavior in civil war should be interpreted less as an instance of social anomie and more as a perverse manifestation of abundant social capital. Finally, Kalyvas elucidates the oft-noted disjunction between action on the ground and discourse at the top by showing that local fragmentation and local cleavages are a central rather than peripheral aspect of civil wars.”

(end)

e. Thucydides and Internal War by Jonathan J. Price

This book is somewhere in between my interest in civil war and “language”. Thucydides had reported how language was changing during the Corcyra conflict.

“The language of the passage is perhaps the most dificult in the entire work. Native Greek speakers in antiquity had trouble with it, and modern interpretations vary to an absurd degree. Yet Thucydides chose each word with great care, and constructed each sentence with great precision. He tried to pack large and complex thoughts into a small space, not in order to be obscure or perverse but to impart both force and elegance to his ideas.

The ideas he attempted to convey strained the capacity of ancient

Greek.

The result is a style which resembles poetry in its compression and power. For the serious reader, close and patient scrutiny of detail is the only way to unlock Thucydides’ thought.

The narrative in 3.81±2 passes from the single instance of a closely observed and carefully recorded stasis at Corcyra in 427 to a generic description of all stasis, a model for both the present war and all time. The transition from the particular to the general is unannounced, and the seam is hardly noticeable.”

(END)

f. Tyranny and terror: the failure of Athenian democracy and the reign of the Thirty Tyrants By Lucas D. LeCaire

The Thirty Tyrants is important to understand, this is a brief paper that explains it.

“Athens, a polis long governed by its proud and unique democracy, was governed by an oligarchy c’onsisting of Thirty Athenians of the aristocratic class, from 404 B.C. when Athens surrendered to Sparta to end the Peloponnesian War (431-404).1 The “Thirty” were entrusted by Sparta to codify the laws of the city for the creation of a new constitution, both oligarchic and loyal to Sparta. The resulting oligarchy, however, did not succeed in drafting a constitution.

The extreme policies and actions of the oligarchs which included the imprisonment, execution, and disenfranchisement of hundreds of Athenian citizens, contributed to their eventual overthrow and earned them the nickname, “the Thirty Tyrants.”

Their iron-fisted rule over Athens lasted only six months, when they were overthrown by an army of exiled Athenian democrats led by the Athenian general, Thrasybulus.

This brief period represents the final climactic episode in the history of Athens’ so called ‘Golden Age’, which included the height of Athenian radical democracy, imperial power, and a cultural flourishing in the fifth century B.C. My research on this period has led me to trace the political history of Athens in the fifth century in order to illuminate the transformation of Athens from an independent polis to the capital of a maritime empire.

(END)

g. Thucydides: The Reinvention of History By Donald Kagan

I’m interested in how history is told, the study of historiography, and this book is about Thucydides shaped the narration of ‘his’ war.

h. Scholars and Warriors: quoting and misquoting Thucydides, by Neville Morley

Interesting short read

i. Thucydides’ War Narrative: A Structural Study by Carolyn J. Dewald

Fascinating book that explores how language changed during the span of the Peloponnesian war(s). Words shape wars

j. The Great Courses, Herodotus: The Father of History, Elizabeth Vandiver

Another one of my favorites from The Great Courses. Herodotus wrote of the conclusion of the war, but he did so with a different style and this shows the early innovations in narrative and historiographical technique.

k. Language, Stasis and the Role of the Historian in Thucydides, Sallust and Tacitus by Lydia Spielberg

“Thucydides’ famous discussion of the degeneration of language during stasis (3.82.4–6) employs a hitherto underappreciated meta-topos: the historian draws attention not only to linguistic inversion but to the self-serving abuse of the topos that virtues and vices are being misnamed. Sallust and Tacitus also employ the meta-topos in their treatments of corrupted language, deliberately distinguishing their critiques from a banal rhetorical commonplace.

This self-consciousness about a central topos of historiography leads historians to reflect on the topos of corrupted language amid stasis as a paradigm of historical analysis, one which must be reformulated to account for crises such as the last century of the Republic and the institution of the Principate.”

l. VIDEO: What I Read and Why I Read It

I did this video walk through of what i read and why I read it. And, what I don’t read and why I don’t read it. It’s really good.

Please watch and let me know what you think of it.